To the end of the earth: A Ship's Diary of a Voyage to Antarctica

- Roger Blum

- 2. März 2022

- 7 Min. Lesezeit

Aktualisiert: 5. Nov. 2023

One hundred years ago, Antarctica was the last unexplored continent on our planet. For centuries, the mysterious southern continent stubbornly held out against conquest and discovery. The darkness of the polar night, which lasts months on end, could plunge explorers into madness. That’s only if they hadn’t perished at the hands of the icy cold. Eaten away by scurvy, slowly freezing to death beside the remnants of their ships, the fast-fading explorers would burn down their vessels to the waterline to eek out the last bit of heat from their boats before their final breath. Antartica is the coldest and windiest place on earth, drier than the Sahara and as cold as Mars. Falling winds race down the polar plateau at up to 300 km/h, with temperatures dropping to minus 80 degrees. Despite these extreme conditions, the ice-cold seas around the continent are among the richest in species in the world. In the Antarctic summer of 2008, I had the opportunity to experience this unique landmass for myself. Not wanting to suffer the fate of my predecessors, I ventured south on board a warm, comfortable ship...

January 13 - Port Stanley, Falkland Islands

51°40´South, 57°50´West, distance from the last harbour, 1,020 km

I have been on the road for almost a week. Berlin, Paris, Rio de Janeiro, Buenos Aires... While the Copacabana and the beach of Ipanema still enjoy summer temperatures, the further south I travel, the more noticeably uncomfortable it gets. The Falkland Islands are located about 650 km east of the southern tip of Argentina in the rugged Southwest Atlantic. The weather is rough: cold and windy. It rains about 250 days a year and a constant wind runs through the area at an average speed of 30 km/h. Winter temperatures average 1.7°C, summer temperatures, 9.4° C. The island’s vegetation reflects the harsh conditions: an abundance of grasses, peppered by low-lying bushes and a few weather-beaten trees.

The Falkland Islands are one of the last undisturbed natural paradises on earth. Here I meet my first penguins. The black-and-white Magellanic aquatic birds, typical of the region, can be seen gracefully gliding in and out the cool waters. At Sparrow Cove in the east of the larger of the Falklands Islands, I visit a colony of gentoo penguins. It is possible to both hear and smell the endearing animals from a great distance. As we approach, their donkey-like screams and the stink of guano fill the air. The millions of white and pink blotches that line the rocks indicate the staple diet of the penguins, krill. It is these small crustaceans that draw the penguins and all of the other celebrities of the Antarctic to these icy waters, including the 100-ton blue whale. The impressive arch that stands in front of Port Stanley Cathedral, made from the jawbone of two blue whales, bears witness to the islands’ colossal visitor. The waters surrounding the Falkland Islands are host to a total of 14 regularly occurring species of marine mammals, including sea elephants, killer whales, sea lions, and several dolphin species that routinely appear among the bow waves of passing boats. Unfortunately, the local dive center has closed...

January 14, 2008 - At Sea

(56°10´South, 56°17´West)

The temperature continues to drop. Aboard our ship, we are fighting our way further south through the grey drizzle, strong winds, and dense fog. Suddenly, breaking the surface of the choppy waters, the hump of a whale climbs over the waves and the pale column of its tail rises majestically into the sky. Perhaps it is a sign; we have achieved Antarctic convergence. Here the cold, dense and nutritious water masses of the south meet the warmer, less nourishing currents of the north. This body of water, which surrounds the entire continent, marks the biological border of Antarctica.

January 15 - Elephant Island

(61°61´South, 54°54´West)

As the morning breaks, the South Shetland Islands are in sight, a wild ravel of rounded, snow-capped domes, soaring mountain peaks, shimmering glaciers and bare rock. The archipelago stretches 500 km northeast to southwest along the Antarctic Peninsula. Although the islands are claimed by Great Britain, Argentina and Chile, they fall under the Antarctic Treaty, which does not allow state sovereignty. Antarctica doesn't belong to anyone. With the signing of the Antarctic Treaty in 1959, the fifth largest continent was declared a nature reserve. In 1982, the protection of the land was extended to the surrounding oceans.

We pass our first icebergs. At around noon a white wall of mist becomes visible in the south and it begins to snow. The weather is extremely changeable. Sometimes the sun shines brightly and a wonderful view of Elephant-Island opens up. Seconds later, the skies close in again, and within a few minutes, the snow returns. Thick fog decorates the horizon. When it lifts, rocky coasts and mountain peaks come into view. Due to the harsh climate, Elephant Island, in the outer reaches of the South Shetlands, has hardly any flora and fauna - only a few colonies of jackass penguins and some accompanying seals live on the rock.

Archtowski-Polarstation, King George Island

(62°09´South, 58°28´West)

In the early afternoon we reach King George Island. Here lies the largest concentration of research stations in Antarctica, including the Dallmann Laboratory of the German Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research. Our visit seems to have caused some sensation in the Antarctic wasteland as a helicopter from the Chilean station circles our ship. Later, another helicopter and a small plane follow the vehicle. In Admiralty Bay we anchor in front of the Polish Archtowski Station and several scientists visit us on board.

The polar station, built in 1977, is named after the Polish scientist Hendryk Arctowski, who was one of the first people to go into Antarctic hibernation as a member of the Belgica expedition between 1897 and 1899. The RV Belgica steamship became trapped in the Weddell Sea and remained so for a full winter, and according to the crew, became a sort of ghost ship. The team was struck by a strange sense of melancholy that took over the boat, which over the long weeks, developed into depression and utter despair. The doctor's diagnosis was polar anemia. The symptoms were essentially the same for all of the crew: increasingly pallor faces, noticeably greasy skin, strong hair growth similar to that of corpses, swollen eyes and ankles, headaches, nausea and insomnia. One man was gripped by the delusion that the other crewmembers wanted to kill him, leading him to take refuge in a tiny niche of the ship every time he wanted to sleep. Another had hysterical attacks that left him deaf and dumb for a time. On June 5, 1899, the Belgian geophysicist Emile Danco died of heart problems, partly due to his fear of darkness. He was buried, as sailor custom decrees, in a sack of canvas with weights attached to his legs so as to weigh him down in an ice hole in the sea. A small Antarctic isle dubbed "Danco Island" - which we headed to the following day – bears witness to the physicist’s story.

In an attempt to combat the symptoms of madness, the men of the Belgica took up the practise of running around the perimeter of the ship. The jogging route later became known as the "Madhouse-Promenade". On top of the calisthenics, Dr. Danco ordered that to counteract the lack of sun, all patients should sit naked in front of a flickering fire for one hour a day and let their skin be irradiated by the light of the flames. This, together with a diet of penguin, seal meat, milk and cranberry juice, was enough to ensure that the condition of the crew did not deteriorate.

January 17 - Palmer-Archipelago

(64°39´South, 62°52´West)

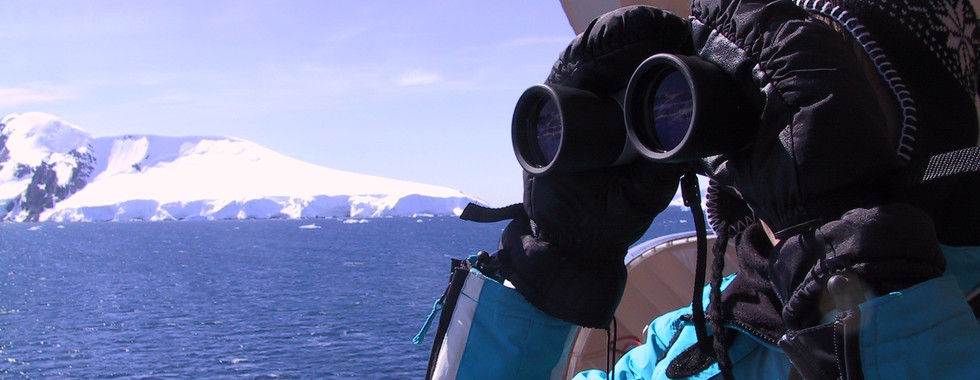

We head southeast to the Palmer Archipelago. The further south we travel, the more treacherous the fairway becomes. Small groups of islands form a tangle of underwater cliffs, as icebergs cross the ship's path and the ocean’s waves push pack ice towards the boat. Not an easy task for our captain. On the ice, penguins can be seen looking on as our ship passes by, while albatrosses fly around overhead in long loops.

We sail through the Gerlache Strait and the Neumayer Channel along the coast of Danco Island. Now, in the Antarctic summer, the sun shines for 24 hours a day. In the afternoon, accompanied by a school of orcas, we reach the southernmost point of our journey, the Neumayer Glacier. Here we turn back to 64°39´ southern latitude and 62°52´ western longitude and head north again. As we sail through the Lemaire Channel, surrounded by high mountain peaks, we repeatedly encounter huge whales searching for food in the nutrient-rich water. I try to distinguish the different species by their wind clouds, but it is a difficult task. The fishing fleets of many nations used to romp around in these waters. Since 1994, when whaling was banned in the region, stocks seem to slowly be recovering.

January 18 – Deception Island

(62°56´South, 60°38´West)

Deception Island, with a surface area of 98.5 km ², is one of the largest and most impressive volcanic islands on earth. The island is the tip of an active volcano, its last eruption occurring in 1970. In the southeast of the volcano ring is interrupted on a width of almost 400 m. Through a strait dubbed Neptunes Bellows, ships can enter the inundated sea crater lake. Just a small distance from the body of waters lay three steep cliffs that rise from the sea, the so-called Sewing Machine Needles.

January 19 – Cape Horn

(55°59´South, 67°16´West)

From Deception Island, we cross the eternally stormy Drake Passage to Cape Horn. Countless seamen have lost their lives here. Men would be swept from the deck directly into the roaring sea by the storms that typify the notorious Furious Fifties that rage between the fiftieth and sixtieth degree southern latitudes. More than 800 shipwrecks, and some ten thousand dead sailors, are said to lie at the bottom of these icy waters. Circumnavigating the Cape can take several weeks and demands great physical exertion. When the German full-rigged ship "Susanna" attempted the journey in the southern winter of 1905, it took the crew 99 days! Many other captains simply gave up, preferring to traverse the west coast of South America via the Cape of Good Hope and Australia. Even William Bligh, famed commander of the Bounty, decided after more than four weeks of battling the Cape on April 22, 1788, to turn back and head for Tahiti via Africa.

But luckily, unlike so many of our forerunners, the waters of Antarctica bade us safe passage. Apart from some dense fog and wind, the crossing was for the most part calm. Even the sea off Cape Horn remained smooth as a baby’s bottom. As we circle the rock of Cape Horn following old sailor custom, the foghorn sounds three times. We have returned to civilization.

Kommentare