The Eight Wonder(s) of the World: "Deep diving" in Milford Sound

- Steven Blum

- 2. März 2022

- 6 Min. Lesezeit

Exceptional natural phenomena are often referred to as "the eighth wonder(s) of the world". One such example is Milford Sound in New Zealand’s South Island, but on this occasion, it definitely deserves the title. The impressive fjord offers recreational divers a unique opportunity to experience the underwater world of the deep sea with relative ease. This is because there is a three to five meter thick film of fresh water, fed by rain and melt water, that lies on top the fiord’s heavy salt water. As much of the fresh water runs through the forest, it picks up tannin from the trees. This makes the top layer of the fiord incredibly dark. In fact, it hardly lets any light through. Therefore, certain life forms can be observed in Milford Sound that you can only usually encounter aboard submersibles deep at the bottom of the ocean. For example, you can meet the world's largest colony of black coral, which usually only occurs 200 m to 1000 m below the water’s surface. Diving to such depths with compressed air alone would be impossible. This makes the waters of Milford Sound a true treasure of marine biology.

In the Pacific Ring of Fire, one of the most active tectonic areas in the world, massive glaciers were formed during the Ice Age. The bodies of ice cut into the mountains, stripping away the rock. Due to the eroding effect of the glaciers, deep channels started to run into the coastal regions, which later filled with water as sea levels rose. In the south of New Zealand, 14 deep, narrow estuaries were formed, which extend up to 40 kilometres inland between the steep rock faces. Today they form the Fiordland National Park. The spectacular coastline is part of the Wahipounamu World Heritage Area, which begins at Martins Bay in South Island and extends as far as Waitutu Forest at the island’s southern tip. The fjords are surrounded by huge mountains that reach up to 2,000 metres above sea level.

The most important tourist attraction of the Fiordland National Park is the 15 km long Milford Sound. It is the northernmost fjord and the only one accessible by road. The thoroughfare, which runs through the 1200-metre long Homer Tunnel, was not built until 1952. Before that, the journey was only possible by boat or over the 54 km long Milford Track. All recent plans to make the fjord more accessible - especially for holidaymakers coming from Queenstown - have fortunately been rejected so as to keep the nature of the region unspoiled. Te Anau, the closest town and so-called gateway to Milford Sound, is 120 kilometres away. The fact that it’s difficult to get there is reflected by the diving prices: a dive in Milford Sound starts at 295 NZ$, which is equivalent to about 200 Euros.

On our first morning, we travel by boat deep through the fjord landscape with stunning views of towering mountain peaks and spectacular waterfalls. The best known is Mitre Peak, located directly at the lowest point of the fjord (265 m), is one of the tallest mountains around Milford Sound at an altitude of 1,692 m. We have excellent weather with blue skies and sunshine. The great visibility allows us to see far into the Sound, and the view is very impressive.

Our ship passes a rock dominated by seals, where a few sea lions are dozing lazily in the sun. Soon we are at the end of the fjord and look out at the Tasman Sea. We make a stop and prepare for the first dive. The water temperatures are around 10°C and we peel on the narrow 7mm wetsuits. They have to be a little tighter than usual; otherwise there is too much space between the skin and the suit for the cold water. An ice vest of the same material thickness serves as additional protection against the cold. We also pull on thick neoprene gloves and hoods. It takes a while to put on all the equipment.

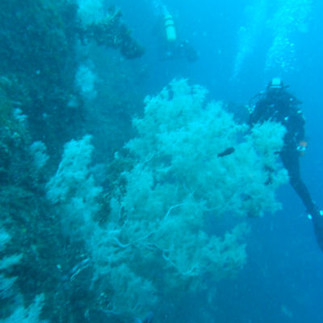

Then we roll backwards into the water. It’s freezing cold. The rock faces here fall steeply into the ocean, which is why it is very deep just a few metres from the shore. Slowly we crawl along the submerged rock face and quickly cross the boundary between fresh and salt water. The impressive landscape continues under water. The undersea scenery is rocky and barren - but that's what makes it so special. The rocks are covered with large colonies of yellow anemone (Parazoanthus sp.), interspersed by the odd vase sponge and red coral.

The underwater world of the Fiordlands contains flora and fauna that is incredibly difficult to see anywhere else in the world

The fjord offers a unique opportunity to get to know the flora and fauna of the deep sea. This is possible because the water that comes from the mountains absorbs tannins from the evergreens, shrubs and leaves from the forest floor. This in turn leaves the fresh water the same colour as tea. As soon as the water reaches the sea, it sits as a thick, dark layer on top of the salt water, blocking light from getting through. This odd phenomenon means the water beneath is incredibly dark and cold, luring marine life that normally lives at far greater depths.

In Milford Sound you can find life forms, which would otherwise dwell much deeper, close to the water’s surface

The most famous deep-sea species that divers can see in Milford Sound is black coral, Antipathella fiordensis. With over 7 million colonies, the Fiordlands are home to one of the largest concentrations of black coral in the world. Some of them are over 300 years old. Normally the coral lives at depths of 200 m to 1,000 m, but here in Milford Sound they can already be observed at just 10 m below the water’s surface. Contrary to what the name might suggest suggests, black coral is not black, but white. Only the skeleton is black. This is covered by a multitude of small white polyps, which are only 1 mm in width.

Vase sponge (Leucettusa lancifer), Red coral (Errina novaezelandiae), Yellow anemone (Parazoanthus sp.)

Black coral takes almost 100 years to grow one meter. Some of the specimens here are over four meters tall. Wrapped around them are serpentine starfish, with red scorpionfish sitting in their branches from time to time.

The black coral (Antipathella fiordensis) looks more like conifer branches than actual coral

Over 150 species of fish can be found in the fjords. Red sea bass and scorpionfish sit stoically on the stony waterbed, camouflaged and lurking for prey. Both fish are bad swimmers, but when scared they can accelerate very quickly for a few meters.

The bizarre tadpole-like Breadula (Fiordichthys slartibartfasti) is an endemic species of fish from the order of the Ophidiiformes and can only be found here in the Fiordlands. The viviparous fish is sometimes called “The Bearded Man”, named after the fictional character Slartibartfast, the designer of the fjords in Douglas Adams' novel "Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy".

We become interested in some belted wrasse fish, which can grow to be quite large, between 30 to 60 cm long. They predatorily feed on invertebrates and are often found swimming after hungry rays, so as to try and steal their food. Apparently they also have a taste for humans; as we swam past they started to bite at our open skin - particularly our lips. These bites are not dangerous, but extremely unpleasant. Of the four divers who went on our trip, two left the water with bloody lips.

Belted wrasse

Fiordland is the southernmost region in the world where lobsters live. The many caves and grottos in the area offer a perfect habitat for the rock lobster Jasus edwardsii. As adults, they can reach up to half a meter long and weigh some 8 kg. The holes and crevices in the rocks offer plenty of hiding places for countless different kinds of the crustacean. Nowhere else in the world have I seen such a so many lobsters.

Rock lobster Jasus edwardsii

Another interesting marine life specimen we were lucky enough to see during the dives was the sea cucumber (Holothuroidea). With over 1200 species, they are the most diverse group of echinoderms, and that includes starfish and sea urchins. Along the coast of Fiordland the brown sea cucumber (Australostichopus mollis) is most common.

Tube anemone (Cerianthus sp.), Brown sea cucumber (Australostichopus mollis), Brittle starfish (Ophiopsammus maculata), Nudibranch (Jason mirabilis), Rock lobster Jasus edwardsii, See urchin (Evechinus chloroticus)

Despite all of the incredible sites, there was one thing that upset the trip: it was so cold that quite quickly I was trembling all over. But still, it is a very special sensation when you stop, look around, and see the snow-capped peaks of South Island’s mountains towering over you. Luckily, they provide jackets and colourful hats in the boat so you can warm up a bit. That’s alongside the fruit, cookies, and hot tea.

We make a final stop by a seal colony and then drive on to a huge waterfall. We pass directly underneath it and the water from the cold glacier falls lightly on our faces. As we start to leave another perfect example of South Island’s stunning landscape, we turn to see that the waterfall has been framed by a rainbow. The scenery both above and beneath the unique waters of this country makes diving in New Zealand simply unforgettable.

Kommentare